According to cognitive neuroscience, our brains are not the most trustworthy when it comes to remembering experiences as they truly were. Every time we try to recall a scene in our heads, we change and reshape it forever based on our more current perspectives. That means the more time that's passed since the actual event, the less likely it is that your memory is going to match reality. Memory is such a fleeting and fragile thing.

That's why it's barely been over a week, but my trip to the mysterious Black Canyon of the Gunnison is already starting to seem like a murky dream. So I'd better just write about it already.

In sparsely-populated Western Colorado, there's a national park that's one of the least-known and least-visited in the country. An average of 190,000 people visit the Black Canyon each year, versus the nearly 6 million tourists that visit the Grand Canyon. That's one of the things I loved about the place- at times, it almost felt like Cat and I had it all to ourselves. In fact, I almost don't even want to tell other people about the existence of the Black Canyon, because the isolation I felt was one of the most beautiful things about the experience.

***

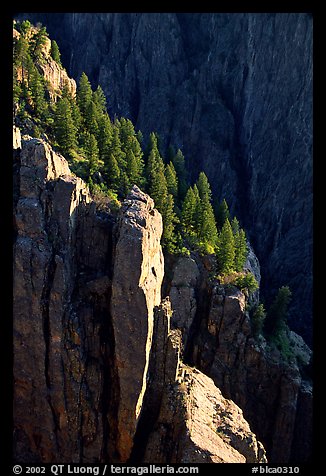

In the early hours of the morning on July 4th, before anyone else was awake, Cat and I ventured to one of the many overlooks of the canyon's south rim and stood at the very edge of a gaping chasm, with huge, vertical walls of granite plunging straight down, thousands of dizzying feet, far past where the light could reach. I gripped the railing with both hands, fought off vertigo, and just stared down into the darkness listening to the distant echoes of a river that I couldn't see. It was one of the most awe-inspiring and terrifying moments I think I've had.

We visited all the different outlooks and hiked around the canyon rim, but all in all, we must have spent a total of an hour or so just wordlessly staring into the canyon.

II

Gazing into the canyon's depths, I tried to imagine what early explorers must have thought when they stumbled across a place like this. The Black Canyon has a rich history, which consists of countless people getting killed by the hazards of the canyon and generally being terrified by the place. The early Ute Indians tended to avoid the Black Canyon out of superstition. They had trails going into the bottom of the gorge but they feared the river, referring to it as "much rocks, big water."

American explorers and civil engineers in the 1800s clearly didn't take that hint. They stubbornly built a 15 mile route through the Black Canyon, after years of dangerous surveying, several people disappearing and deserting, and saying it was impossible to do.

There are reports of countless hazards and casualties for the mostly-immigrant laborers blasting out a roadbed and laying down tracks. When it was finally built, it was the most dangerous route in the country- avalanches, rock falls, and trains getting swept into the icy Gunnison River were a constant risk for railroad engineers and passengers.

Rudyard Kipling was one of these passengers in 1889 and wrote:

"We entered a gorge, remote from the sun, where the rocks were two thousand feet sheer, and where a rock splintered river roared and howled ten feet below a track which seemed to have been built on the simple principle of dropping miscellaneous dirt into the river and pinning a few rails a-top. There was a glory and a wonder and a mystery about the mad ride, which I felt keenly…until I had to offer prayers for the safety of the train."

Fortunately, although the cost of human lives didn't seem to be much of a factor, a lack of profits caused the Black Canyon railroad to be discontinued and eventually torn up in 1949. This portion of the canyon is now preserved by the National Park Service, freeing up adventurous folk to voluntarily risk death in other ways trying to venture in there with mere climbing and/or camping gear.

III

So the collective memory of this place very closely matched my own - terrifying, and yet mysterious in a way that seemed to draw me in. Cat and I hiked the Warner Point Trail on the canyon's south rim, a rocky uphill affair filled with wildflowers, ancient juniper and pinyon pines. And we discovered that Warner Point Trail ends in one of the few designated routes into the canyon, aptly named the Warner Route. But we, along with any other average hikers who might have wondered about continuing on the route, were stopped by a sign posted in front of it to keep us out. Only hikers with wilderness permits were allowed to go any further. All others should turn back on the trail to go back the way we came.

Still, we stood in front of that sign for a long moment, and I was inexplicably drawn to venture a few steps beyond it to peer down at a steep, treacherous-looking path descending into the inner canyon- getting narrower as it went, with very few handholds, until we couldn't see where it went without actually starting down the path.

Part of me wanted very badly to ignore the sign and continue walking, but logic ultimately won out, along with the desire not to get lost inside the Black Canyon without a permit, proper supplies, water, or a way to get rescued. For the first big roadtrip vacation that my friend had trusted me enough to accompany me on, it wouldn't have been the best of experiences.

For the time being, we stuck to taking absurd risks like climbing onto a ledge of the canyon rim, or doing a yoga pose at the edge of a crevasse, to take some cool photos. The National Park Service, in the interest of maintaining the natural beauty of the canyon, did not install railings on virtually 99% of the entire thing, thus making stupid decisions quite easy on our part.

In a similar vein of "We've given you ample warning, so it's your own damn fault if you die while doing this", all the descriptions of the inner canyon on NPS.gov seemed to advise against going in altogether:

There are no maintained or marked trails into the inner canyon. Routes are difficult to follow, and only individuals in excellent physical condition should attempt these hikes. Hikers are expected to find their own way and to be prepared for self-rescue. While descending, study the route behind, as this will make it easier on the way up when confronted with a choice of routes and drainages. Not all ravines go all the way to the river, and becoming "cliffed out" is a real possibility.

Despite these warnings, I learned later that wilderness permits were free, and surprisingly easy to get- talk to a park ranger to get one. All I could think of after that was "We're going back next year, getting permits, and going in." We talked about it. We discussed what it might take to make it happen. And finally, we decided to make plans. Next year, with a crew of at least 4 people, at peak physical fitness and with supplies to last us at least 2 days.

It's hard to explain why, but gazing into the mystery of the Black Canyon just seems to tempt certain people to wander in to see more. To see what those early explorers saw, and what the many species of birds flying freely in and out of the canyon take for granted every day. That's one of the things I couldn't possibly appreciate about this place until I actually saw it for myself- the Black Canyon of the Gunnison is deep, craggy, dangerous- and filled with life. Towering fir and aspen trees were growing stubbornly along impossibly steep walls dropping thousands of feet down, like a vertical forest, which all seemed to be nourished by the deadly, fast-moving Gunnison River rushing through the ravine floor. Even knowing I was at the height of a 2,000+ foot drop into all of this, staring down, it felt less like the call of the void, but more like the call of the wild.

Only those who risk going too far can possibly find out how far they can go.” — T.S Eliot

No comments:

Post a Comment